Climate & Sustainablity

African Delegates Say COP30 Promises Still Fall Short for The Continent

African deleagtes at COP30 stress that global climate diplomacy still lags behind Africa’s realities, demanding finance, fairness, and action.

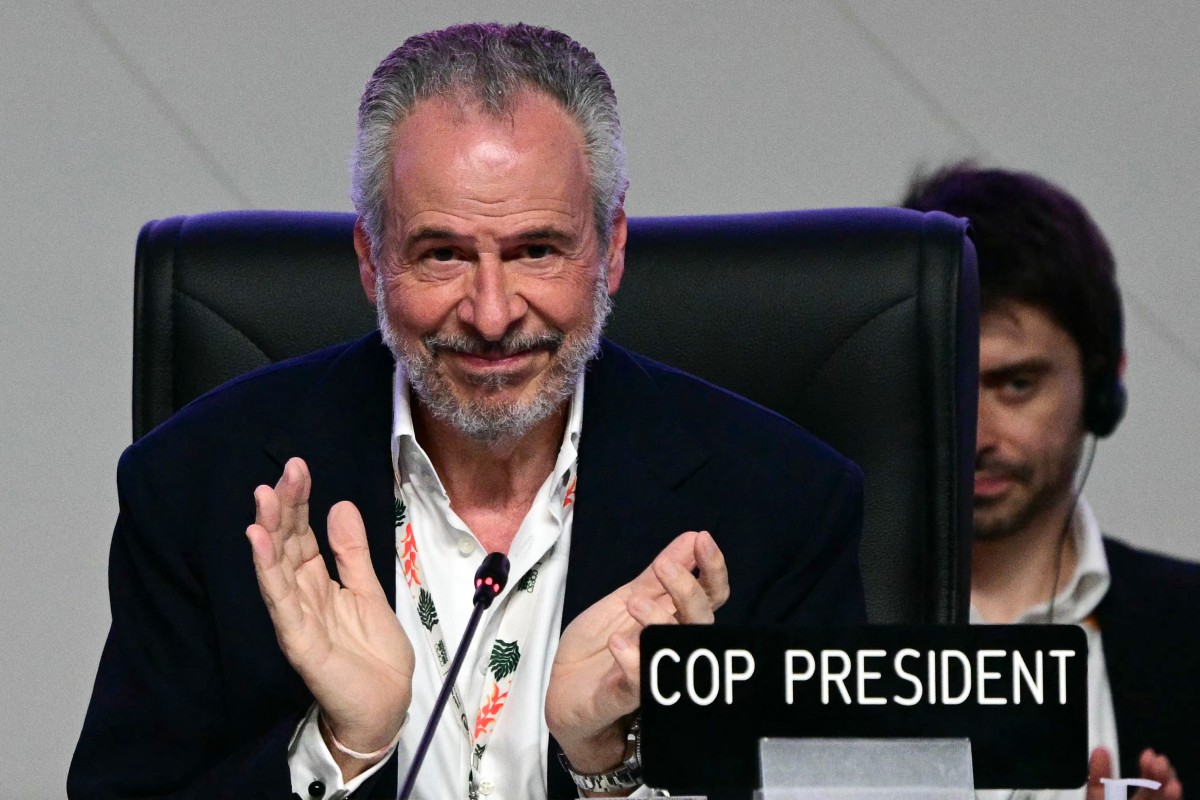

At the close of Belém’s COP30 besieged by fire, protests, clashes, catering hiccups and a logistical fiasco, African delegates packed their documents and rolled up their badges with a rather familiar mix of resolve and frustration.

The summit, they said, delivered notable advances on adaptation and accountability. But it left Africa with the same unsettling questions it brought to Brazil: Will the money come? Will the world move fast enough? And who, ultimately, will bear the cost of the global transition away from fossil fuels?

Interviews with delegates including activists, climate journalists, policy leaders and negotiators, who spoke to Africa Energy Pulse revealed an unease that global climate diplomacy, however well-intentioned, continues to move at a pace and structure misaligned with African realities.

Promises Must be Backed by Delivery

Rt. Honourable Sam Onuigbo, a principal architect of Nigeria’s Climate Change Act (CCA), said COP30’s adaptation gains could be transformative, well… if they are delivered.

He said that for Africa, where climate vulnerabilities are pronounced, the increased focus on adaptation finance is crucial and with the introduction of monitoring tools such as the Belém Mission offers a framework for enhanced transparency and pressure on governments to meet their climate obligations.

Moving down to Nigeria, the climate champion said the 2035 timeline is not too slow for Nigeria, given the country’s legally established 2050–2070 net-zero target. “The agreement to triple adaptation finance is highly significant,” he said. “It creates an opportunity to invest in renewable energy, transport and power-sector reform; all essential components for reducing pollution and strengthening resilience.”

But access remains the obstacle. “The priority now lies in fulfilling these pledges and removing the barriers that impede countries from accessing funds,” he said.

The failure to secure a fossil-fuel phase-out roadmap did not alarm him. Nigeria’s transition, he believes, will not occur overnight. “Natural gas remains our transitional fuel,” he noted.

What matters, he said, is that COP30 launched the Belém Mission, which shifts climate commitments toward measurable accountability. “The global momentum is toward concrete results and Nigeria’s timelines remain appropriate and balanced between development needs and climate obligations.”

Honourable Onuigbo singled out fairness as the grounding principle for the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM) adopted at the summit.

He said, “Vulnerable groups such as women, youth, indigenous peoples and low-income communities must remain central to transition planning, all enshrined in the country’s Climate Change Act.''

For the mechanism to succeed, he asserts that the government must prioritise social protection, job security, reskilling and economic diversification. “Genuine progress requires resilience, justice and tangible implementation,” he said.

He added that COP30 embodied a move from ambition to execution, but warned that translating international commitments into national action remains the continent’s greatest challenge.

Multilateral Process Failed to Deliver Africa’s Financing Needs

Suleiman Arigbagbu, Executive Secretary of Human and Environmental Development Agenda (HEDA) Resource Centre offered a sweeping critique of the process. For him, the negotiations showed a systemic unraveling of the core principles that once underpinned international climate cooperation.

He said the decision to triple adaptation finance was neither surprising nor reassuring for keen observers. It merely confirmed what he sees as a steady erosion of the foundational principles of the UNFCCC regime.

“Since COP21, there has been a gradual shift from mitigation support to a narrower focus on adaptation. This was never the spirit of the Convention. The philosophy of common but differentiated responsibilities is being weakened sometimes subtly, sometimes openly,” he stated.

He pointed to the numbers where Africa requires between $250 billion and $400 billion a year to cope with climate impacts. It receives $25bn–$28bn, about 10 per cent of what is needed. He said, “Even the flagship pledge of $100 billion a year in climate finance has never been fulfilled: not even 30 per cent has been mobilised.”

Arigbagbu said the deeper injury lies in the quality of finance now on offer.

“What was supposed to be obligation-based support has become a marketplace of loans and debt-heavy instruments. We are being asked to borrow our way out of a crisis we did not create,” he said.

He stressed that the history of climate finance does not inspire confidence.

“This new tripling of adaptation finance being pledged if it goes the same way as the initial Adaptation Fund, the Green Climate Fund and so many other commitments, the money will not really come in and we have seen this pattern before.”

Arigbagbu argued that global finance has drifted away from grants and obligation-based support into market-driven, debt-heavy instruments that deepen vulnerability. He said the broader failure is systemic.

“It’s a setback for Africa, but not one that cannot be overcome. Africa needs to redirect its focus, because COP after COP, the multilateral process has failed to deliver the kind of financing obligations that support Africa, and other least-developed countries who are least responsible for this crisis and least able to cope with it,” he said.

On the absence of a fossil-fuel phase-out plan, Arigbagbu said the outcome exposes a widening disconnect between global ambition and African realities.

“People want Africa to move quickly away from fossil fuels, yet the continent was never supported to diversify in the first place,” he said. But he also warned that prolonged dependence on oil and gas carries its own risks, including stranded assets and deepening vulnerability.

He, however, welcomed the adoption of the Just Transition Mechanism but insisted it must prioritise workers, fairness and economic transformation.

Adaptation Finance is Moving Too Slowly

To Olumide Idowu, CEO of International Climate Change Development Initiative (ICCDI) Africa and climate justice activist, COP30 was an important, if incomplete, structural shift.

“The failure to secure a fossil fuel phase-out roadmap is a major setback for countries like Nigeria that need clarity and ambition to guide a fair and inclusive energy transition. While some may frame the delay as “breathing room” for development, the reality is that without a clear global commitment, vulnerable nations remain trapped between rising climate impacts and slow structural change.”

He clarified that this outcome weakens the fight to keep 1.5°C alive and underscores the need for African voices to push even harder for accountability, equity, and real transition pathways.

Idowu argued that tripling the adaptation finance is a welcome step, but for Africa and Nigeria it still doesn’t mature up to the urgency the continent faces on the frontlines of droughts, floods, displacement, and food insecurity.

“Waiting until 2035 is simply too slow as our communities need scaled-up, accessible finance now, not promises stretched over a decade. Without accelerated timelines and direct funding to local actors, this commitment risks becoming another delayed lifeline for those already living the realities of climate breakdown.”

Nigeria, he said, must embed community voices, especially workers, women, and frontline groups, into every stage of the Just Transition Mechanism, invest in skills development, social protection, and locally driven green industries so no one is left behind as fossil-dependent sectors decline.

“The priority is having transparency and accountability must guide all transition decisions to ensure that the benefits truly reach the people, not just institutions.” He concluded.

Aspirational Rather Than Actionable

Ibrahim Muhammed, a Resilience and International Development Officer, said COP30 again revealed an increasing gap between global ambition and conditions on the ground.

“The outcomes of COP30 once again showed the persistent gap between global commitments and Africa’s climate reality. Although the final text acknowledged the need for enhanced adaptation finance, strengthened early warning systems, and support for climate-affected populations, the pace and scale remain inadequate for a continent already facing increasing climate risks.” he said.

He added, “Without accessible finance or mechanisms that actually work for us, much of this remains aspirational rather than actionable.”

The youth climate leader said that African youth and civil society pushed climate mobility, loss and damage and community-level adaptation, but African governments must assert stronger leadership ahead of COP31 to turn demands into frameworks that deliver justice, direct financing and tangible progress for frontline communities.

Africa is Beginning to be Heard

Joy Ify Onyekwere, Founder of Climate Justice Africa Magazine, the tripling of adaptation finance means the Global North is beginning to listen and that the buildup from the Africa Climate Summit (ACS-2) was not in vain.

She called the decision a validation of Africa’s long-standing posture: that the continent emits little but bears disproportionate impacts. The finance boost, she said, could strengthen early warning systems, agriculture, water management and community resilience.

However, she was pragmatic on the timeline. She said, “I wouldn’t say it’s slow as it gives us space to pursue our priorities step by step. We don’t have all the time, but we can maximise what we have if each year is tied to clear emission-cutting goals.”

Onyekwere acknowledged the absence of a fossil-fuel roadmap but noted that Nigeria has demonstrated climate leadership by being the first West African nation to submit NDC 3.0.

“We cannot talk about a just transition without fossil fuels. The lack of a roadmap may affect Nigeria’s efforts, but I believe we have smart leadership at the National Council on Climate Change (NCCC). We were the first West African nation to submit NDC 3.0, which tells you we know what we are doing,” she added.

She added that Nigeria has been building partnerships around the energy transition long before delegates arrived in Belém. “We shouldn’t be too worried about the roadmap missing from the Mutirão declaration,” she said. “There is still room for development.”

The founder reiterated that the real work lies not in waiting for global timelines, but in strengthening domestic institutions, partnerships and capacity. Where Onyekwere was most forceful was on the JTM, which she said must be grounded not just in climate policy but in human development.

“We need to develop human capacity and ensure workers in the energy sector are safe, supported and prepared for what comes next.” She stated.

But for her, the heart of the transition is youth. She harped on human capacity, skills and youth inclusion. “Nigeria needs to train young people, make the sector relatable, build bootcamps that inspire them to pursue green jobs and circular economy businesses,” she said.

A Continent at an Inflection Point

The discussions all point to a continent caught in the middle of competing pressures: devastated by intensifying climate impacts, constrained by limited financial, technical and technological capacity, and navigating a global transition that could either uplift or further marginalise it.

COP30, many believe, delivered some form of progress but not at the scale demanded by African realities. The attention now gravitates towards COP31 and many delegates posit that Africa as a collective must move from reacting to global processes to shaping them, including demanding faster finance, clearer transition pathways and a fairer system that recognises the continent’s disproportionate burden.

Related Stories

New UK Climate Finance Accelerator Boosts South Africa's Green Transition

ADB, São Tomé and Príncipe Sign $18m in Adaptation, Energy Transition Financing

African Delegates Say COP30 Promises Still Fall Short for The Continent

Renewables, Finance and More: Key Agreements from the Historic G20 Summit Declaration

Sign up for our news letter.

Get the latest news, expert analysis, and industry insights delivered straight to your inbox. Join thousands of professionals shaping the future of energy.

By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.